« A cellistic high-flyer with fine creative ability who has phenomenal command of his instrument »: this is how music critic Norbert Hornig described the young cellist Gabriel Schwabe five years ago. Schwabe, born in Berlin in 1988, has maintained his flying height and consolidated his excellent reputation – also thanks to the highly acclaimed albums he has recorded on the Naxos label. He has been under contract there since 2015. At the ICMA awards on April 21 in Wroclaw, he will represent Naxos, ICMA Label of the Year. Frauke Adrians, of the magazine ‘das Orchester’, ICMA jury member, talked to Gabriel Schwabe.

Gabriel Schwabe, on your latest CD you play ballads by Shostakovich and Prokofiev, among others. Do you feel particularly at home in this music?

I have a natural affinity for the 20th century – there’s a repertoire there that I have the easiest access to. But that doesn’t mean I’m locked into it. In general, I’m also very comfortable with anything romantic. As a soloist, you’re well advised to have a broad range anyway. And as a cellist – unlike with the piano or violin – you are in a position to know all the essential works of literature. If you then have the freedom to occasionally discover something new, you can consider yourself lucky. I’m happy to take up something more obscure if it’s music I’m one hundred percent convinced of.

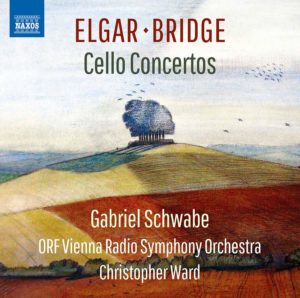

Like the cello concerto Oration by Frank Bridge on your second most recent CD?

Exactly. That’s music that’s really worth rediscovering. With my label Naxos, I tinkered with a concept for this CD for a long time. In retrospect, it’s amazing that we tinkered for so long, because the pairing of Bridge – Elgar is actually obvious. Both composers wrote their concertos under the impression of the First World War, and their works are close to each other in terms of content and emotion. Only, Bridge’s Oration was almost forgotten soon after its premiere, while Elgar’s concerto has remained well-known and popular throughout.

Exactly. That’s music that’s really worth rediscovering. With my label Naxos, I tinkered with a concept for this CD for a long time. In retrospect, it’s amazing that we tinkered for so long, because the pairing of Bridge – Elgar is actually obvious. Both composers wrote their concertos under the impression of the First World War, and their works are close to each other in terms of content and emotion. Only, Bridge’s Oration was almost forgotten soon after its premiere, while Elgar’s concerto has remained well-known and popular throughout.

When one hears Elgar’s Cello Concerto, one inevitably thinks of Jacqueline du Pré. Is she – or are other old masters of the cello – a role model for you to emulate?

Jacqueline du Pré – and I could name other ‘old masters’ – are an important source of inspiration for me. Only, when you play the Elgar concerto, you shouldn’t make the mistake of trying to follow in du Pré’s footsteps. I think every cellist and every cellist comes to their own personal interpretations. For me, studying great predecessors and their recordings is very enriching and spurs me on to find my own musical path.

Does Naxos give you freedom in choosing your CD repertoire?

Yes! We prepare CD projects jointly; this was already the case for the CD with Saint-Saëns’ works for cello and orchestra, which I recorded together with the Malmö Symphony Orchestra conducted by Marc Soustrot in 2017. The collaboration with Naxos is excellent; with this label I can record any of my CDs with top-class orchestras and great conductors.

When Naxos was still new, at the end of the 80s and into the 90s, the label did not have a good reputation, at least in Germany, among quite a few musicians and record buyers. The CDs were pleasantly inexpensive, but in return you would get mediocre recordings with mediocre artists…

These prejudices have never interested me, they do not correspond at all to my own experiences. Naxos CDs were among the first that I bought as a pupil and student, and not only because they were so cheap. I have always liked the fact that Naxos focuses on the repertoire and not so much on the artist or ‘classical star’. I have found that this focus on repertoire appeals to a certain type of musician. Everyone approaches it with great seriousness and earnestness. In addition, Naxos is very broadly based – there is always something new to discover as a listener, but also as a musician! I am very happy that I was signed to this label and that a great partnership has grown out of it over the years.

How did you come to play the cello? Was it always your dream instrument according to the motto: cello or not at all?

My mother is a piano teacher, so the piano was just around in our house, so I started playing it as a child. Later, the violin came along, but I had no natural aptitude for it – for example, I could never vibrate on the violin! I then found the cello to be a natural upgrade, and it was exactly the instrument I chose for myself when I was eight years old. And fortunately I was able to learn to play the cello at my school in Berlin-Neukölln in an AG.

Which teachers were later the most important for you?

Which teachers were later the most important for you?

Essentially two: Catalin Ilea at the UdK Berlin, to whom I came very early – an icon of musical education, that was a formative time for me. And Frans Helmerson at the Kronberg Academy. Both taught me in an incredibly gentle and loving way, but at the same time made me realize that they were also asking a lot of me. Interacting with both of them also made me realize that I also want to teach myself, to impart and pass on my knowledge and skills.

I was lucky enough to experience Janos Starker during his last visit to Europe – that was a very formative encounter. Other important teachers for me were, for example, Gary Hoffman, who came to Kronberg as a guest lecturer, and Heinrich Schiff.

And when did you realize that your career was not heading for an orchestral position but for a soloist career?

Such a thing can hardly be planned! When I was 14 or 15, I had the idea for the first time that I could make playing the cello my profession, and then I just stuck to it with a lot of idealism and joy. Then came the one or other competition that went very well. Everything else fell into place. Luck is also part of it!

You play a Guarneri cello from 1695. Is it exactly the right instrument in all cases – or do you occasionally flirt with a more modern cello for newer repertoire?

My Guarneri is my dream cello. It was up for sale a few years ago, and I was lucky enough to find a family who could provide me with this instrument. I know many colleagues who have several cellos and bows – but I like to have exactly one cello and one bow with which I feel I can really do everything. It may be that the instrument also has weaknesses, but I can deal with them well.

You not only give concerts and record CDs, you also teach in Maastricht and Cologne. Both are not exactly around the corner from your hometown of Berlin. How do you manage it all – in terms of time, logistics, energy?

It does indeed require a lot of logistical effort, but at the moment it’s working well. It gives me a lot of pleasure and also gives me a lot in return. Of course, I’m on the road a lot and have already missed flights because the airline staff couldn’t cope with the cello. But that’s just part of it. I thoroughly enjoy traveling, but it is also exhausting.

The Corona years 2020-2022 were very difficult for most freelance musicians. How did you get through this time?

I was privileged by my tenure as a university professor, and my wife also teaches at the university, so our financial worries were not as great as those of many colleagues. But it was challenging not to be able to play publicly for such a long time. But my wife – she is a violinist – and I also used this phase to immerse ourselves in music, to rehearse, to get to know works. Then, in the middle of the lockdown, a very special collaboration arose for me with the ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra Vienna on the cello concertos by Bridge and Elgar. Until a week before the project began, I didn’t even know if I would be able to enter Vienna under lockdown conditions! But it worked out.

What musical project do you have coming up next?

In the short term, I have a big Beethoven project coming up. I consider that a privilege – it’s incredible what happens musically in Beethoven’s works. He set milestones! I have to admit that as a child I didn’t understand Beethoven at all. It took me a long time to get closer to him. Today, for example, when I think of the Cello Sonata No. 5 in D major, op. 102.2 – and especially the fugue – I still wouldn’t say that I understand everything that happens there. Beethoven has to be discovered for oneself, again and again. The interaction with the performer is the crucial thing.

I also try to convey this to my students: Always look at the score with a fresh eye, discover each work anew for yourself, even if it’s only about details. Then you stay alive as a musician!